This week, news outlets and social media across the world is covering the protests in France, and rightly so. Without delving into the nuances, France is seeing protests that have also been turning violent, after the police had been accused of murdering a teenager by shooting.

While recent reports suggest France is in for a relatively calmer night after the protests, parallelly in our country, many parts of the state of Manipur has also been witnessing violence - for over three months now. The government had resorted to calling in the central forces but their indiscriminate shoot-to-kill action has increased deaths but provided no viable solution to the conflict.

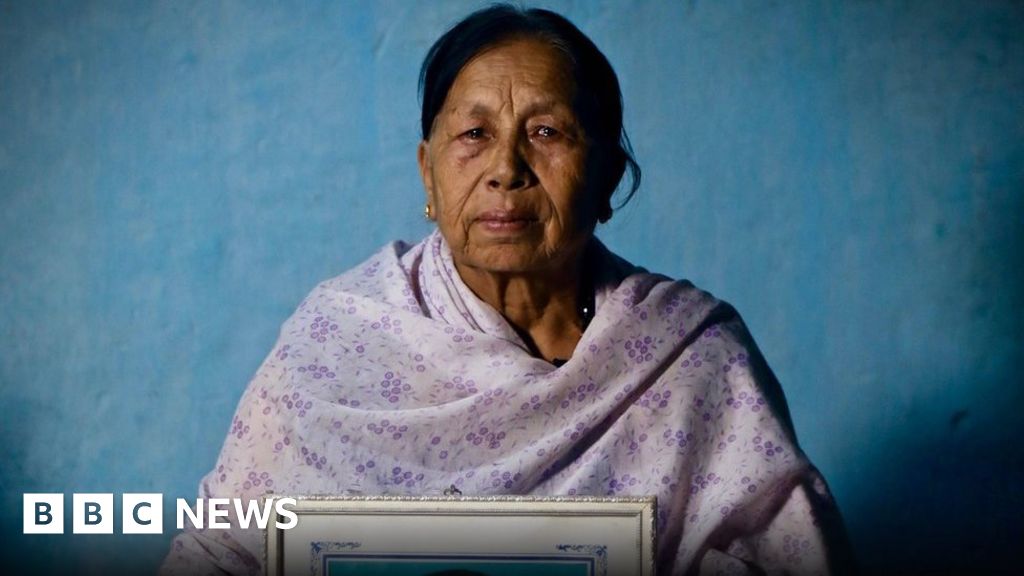

In fact, almost twenty years after Manipur's Meira Paibis, the women torchbearers or the mothers of Manipur had staged a protest with a phot that no one would easily wipe of other consciences, Manipuri women have again demanded peace in the state.

The ethnic conflict is complicated to explain - but compiling from several sources, it runs deep, and it runs back at least as old as the British Raj, when the colonisers intervened in the existing system to divide the communities. Below is a quote from the Caravan's commentary on the issue.

Two diametrically opposite versions of history fuel the conflict over the issue of separate administrations. The Meiteis believe that all of Manipur, hills and valley, was part of Kangleipak for centuries before the British took control of the princely state, in 1891. They blame the British for separating the hills from the valley, since, under the system of administration they imposed, the king had no authority over the hill areas, from varying parts of which his predecessors had previously extracted tribute. The Kukis and Nagas, on the other hand, blame the British for artificially uniting the hills and the valley, claiming that the appointment of local liaison officers, called Lambus, to act as intermediaries between the British and tribal chiefs undercut the independent authority that their traditional institutions had exerted over the hills before 1891.

Just like everyone else, we urge the government to intervene responsibly and resolve the conflict without more damage to life, property and rights of the communities - but from our end, we have to flag and highlight some of the violations of basic rights. In our last chapter of TypeRight had talked about steps to make Internet as a basic right, we also mentioned how internet shutdowns would work exactly opposite to this cause - because it restricts freedoms, economic and political.

The HRW report starts with this quote:

"When the internet is shut down, I have no work, do not get paid, cannot withdraw any money from my account, and cannot even get food rations." —H.K., 35, a Dalit woman with five children, Rajasthan, September 2022

This is a direct result of linking services that are as basic as food distribution and unemployment benefits to the internet - which is deadly when combined with lack of access. And in these cases, this access block is intentionally done, in an area that is already reeling from conflict, displacement, and resulting poverty and hunger.

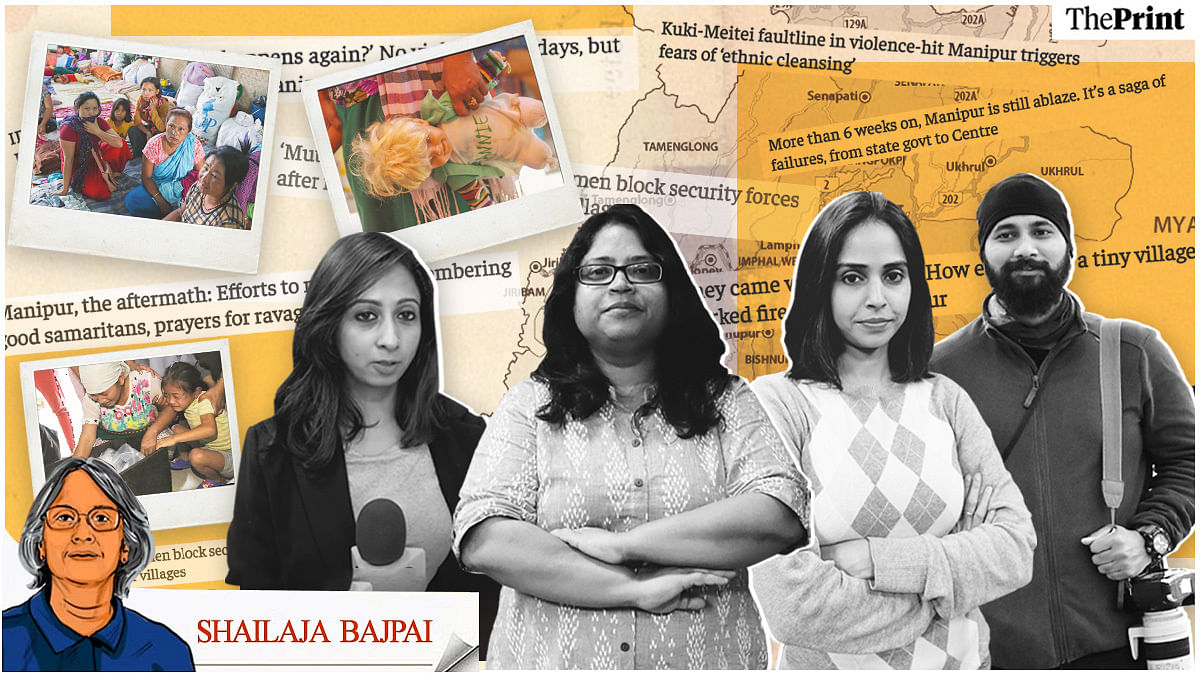

Moreover, they prevent people from accessing information and communicating with each other, which can make it difficult to resolve conflicts peacefully. It violates these fundamental rights of freedom of expression - and of journalists trying to report violations, basically amounting to censorship of people and the press. In this article, ThePrint mentions how they managed to report from the ground in Manipur while facing a shutdown:

But when you’re travelling, especially to remote areas where internet connections are invariably poor, how do you send back reports and long analytical pieces for publishing at the required speed? “Time is important in violent situations,” says Das Gupta. Reporters and editors have to be inventive. Das Gupta used contacts in the state secretariat to send her pieces, although this was limited; Hasnat knew local reporters. They also sent stories sentence by sentence in messages. In Delhi, editors took dictation over the phone.

And such shutdowns have been quite common in the country. Look at this statistic from the same report:

This is exacerbated by the fact that most Indians rely on mobile connectivity for any internet access: "Most shutdowns involve only cutting off access to the internet on mobile phones. But this translates into a near-total internet blackout in that region because 96 percent of subscribers in India use their mobile devices to access the internet, while only 4 percent have access to fixed line internet."

Are there any other costs? If the incursions to liberties and freedoms aren't enough, new reports suggest huge material costs involved:

We used Internet Society's new tool, the NetLoss Calculator that attempts to use available datasets to estimate a quantified cost of internet shutdowns. Running the calculator till the end of last month, the GDP loss ran to six billion dollars, and several loss of employment opportunities from the loss of connectivity.

In Manipur, as this reporter for Outlook Magazine was told by an IT entrepreneur from the state, "Apart from all the normal transactions stopping, businesses relying on the internet have come to a standstill. We need the internet for paying back our loans. Consumers are not able to pay us. Filing of GST has been affected as we are not able to file it on time because there is no internet." This is the same case for people who could not pay for treatments at hospitals, arrange for their payments even if they stay outside the state - and the damage is not something easily reversable.

When we talk of Digital India, or keep highlighting these achievements in international forums like the G20 and the branding of Azadi ka Amrit Mahotsav, we should remember that the loss of connectivity takes us several steps back from several aspects of freedom.

As of the last update before this blog was posted, the shutdown was extended by the court, yet again.

News from around the country

Two uplifting stories of how the digital has helped these women in Tamil Nadu transform their education and employment, one from Sivakasi, and the other from Villupuram:

Kerala government has decided to take steps against people spreading disinformation -

but this brings in the larger question of how we designate and delienate true news and the fake -

From DEF's offices and centers:

In this new DEFDialogue, listen to one of our SoochnaPreneurs talk about her struggles:

Here are some pictures from our training camp for farmers in Assam:

And finally, don't forget to follow and share our Digital Artisans of India Awards!

Until next week!

might be?](https://sk0.blr1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/sites/1394/posts/714526/dbc8de4c-5c50-411f-aba0-55cfb74a692d.jpeg)

Write a comment ...