Many parts of our society have been changed by the fast development of the internet and digitization, especially in the realm of economics. This includes changes in company practices, changes in consumer behaviour (with consumers becoming prosumers), the introduction of digital platforms, and the establishment of the network economy.

When it comes to businesses, societies that are driven by data present both huge potential and challenges. Frameworks and tools that can evaluate the potential for data-driven innovation and value creation need to be established in order to make the most of these changes and capitalise on them. For digital transformation, performance, evolving production systems, decision-making in real time, and the generation of unstructured data from social networks, data is an essential component.

Platformising is something that we see emerging over the past decade - online structures that radically restructure our activities, of work and production, and entertainment and socialising - also often going by under the name sharing economy. The definition is so diverse, that a platform could be anything from Pirate Bay to Netflix, or Wikipedia to Byju's, Amazon (shopping/web services), etc. In most cases, the platform acts as an intermediary rather than an a full employer or full product themselves. Platform operators in the "sharing" economy have unprecedented control over pay and job organisation. Similar to how artists sell their work through galleries, the fast expanding mobile app stores and user-generated content platforms such as YouTube and Instagram are organised as digital consignment industries. Business, politics, and social contact are all part of the "platform economy" or "digital platform economy," which describes a wide range of activities made possible by digital technology. Uncertainty surrounds the nature and future of platforms despite the profound impact they will have on society, markets, and businesses.

Why this uncertainty? Here, we look at two aspects - labour and the environment.

The hidden labour in AI, and the precariat being more precarious is something DEF has brought into highlight during our work with Alan Turing Institute on Data Justice Policy and Practice in India. It is also published as a book, which can be viewed here.

The unsettling truth of welfare programme decision-making driven by machine learning is brought to light by Deepak P, who illuminates the negative effects of AI development on the working class. He stresses how contact centres and other interactive workforces will eventually become unskilled. Whether it's caste in India or race in the West, Deepak stresses that these systems are frequently built by an elite labour that is disconnected from everyday realities.

Here is a quote from the book:

IT companies collect, collate and organise large amounts of data; with the introduction of AI-operated systems and the growing need to transform more services into AI-managed resources, I happened to be involved in projects involving what could be called a paradoxical development. Customer care workers, who are employees at the bottom of the IT pyramid, were asked to collect data that could be used to create an automated customer care system. Human workers were collecting data as raw material for a machine that was about to make them jobless. This ironical instance and system design can be evidenced across the world in different industries that are moving toward AI-backed functioning. The service provider Uber has begun envisioning a long-term plan of introducing driverless cabs. In order to achieve this goal, they would collect and utilise the data that is generated by drivers. Essentially, this means a loss of the dignity and agency of the worker and the driver. This may also be read alongside observations in early Marxist literature about how rampant division of labour reduces the agency, self-respect and satisfaction of workers. With data-driven AI, this is being operationalised at never before seen scales and in ways unforeseeable in the pre-AI era.

The facility and use of human input contributed to efficiency and improvement and considered the worker as a respectable person. On the contrary, AI de-skills the call centre solution pipeline, and while it may be able to address several simple issues, it would need to fall back on human expertise when the going gets tough. But then, eventually, after several years, there may not be any human expertise to fall back on since their learning process has been automated by the very same AI.

Yanis Varaoufkis, former finance minister of Greece who stood up to the Troika and their austerity measures, published a book last year titled Technofeudalism:

He warns of how AI would be employed to bust unions just as it detects and busts viruses. Humans demonstrated their intelligence by programming AI algorithms that could decipher the proteins of a deadly bug and produce an efficient antibiotic entirely autonomously. Who could have thought that massive corporations like Amazon would jump at the chance to pinpoint and eliminate jobs in their supply chain when artificial intelligence indicates a greater likelihood of unionisation?

He also mentions that if artificial intelligence is left unregulated, platforms such as Amazon Web Services (AWS) could gain control of the digital economy's essential resources and function as rentiers. Amazon Web Services (AWS) charges businesses who use its platform for on-demand cloud computing, but it keeps exclusive rights to its analytics and artificial intelligence technologies. Generating money in this rentier economy is more about collecting fees than actually generating something of worth. When it comes to regulating driver-rider matching algorithms and charging monthly rentals for access to media material, other platform companies like Uber and Netflix also exhibit rentier traits. According to Varoufakis, this rentier dynamic has the potential to centralise power in the hands of unaccountable corporations, hollow out industries that cannot satisfy Big Tech's demands, and transfer revenue from labour to capital.

Now, having recently observed yet another World Environment Day, we can pause and reflect on the actual planetary impact of the new cloud and platform technologies, now racing to be increasingly supported by AI.

ChatGPT consumes over half a million kilowatts of electricity each day, and every request you make also requires the servers almost a bottle of water each in cooling down.

Already, predictions indicate that the AI industry's power usage would soar, possibly reaching 85-134 TWh yearly by 2027. It is estimated that data centers accounted for 1% of energy-related global greenhouse gas emissions and approximately 300 metric tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2020. In addition, with companies trying to work on the efficiency side by binging in new models of chips that can handle AI better, the older hardware becomes e-waste, which most of the world is still figuring out ways to handle.

Heat is the waste product of computation, and if left unchecked, it becomes a foil to the workings of digital civilization. Heat must therefore be relentlessly abated to keep the engine of the digital thrumming in a constant state, 24 hours a day, every day. To quell this thermodynamic threat, data centers overwhelmingly rely on air conditioning, a mechanical process that refrigerates the gaseous medium of air, so that it can displace or lift perilous heat away from computers. Today, power-hungry computer room air conditioners (CRACs) or computer room air handlers (CRAHs) are staples of even the most advanced data centers. In North America, most data centers draw power from “dirty” electricity grids, especially in Virginia’s “data center alley,” the site of 70 percent of the world’s internet traffic in 2019. To cool, the Cloud burns carbon, what Jeffrey Moro calls an “elemental irony.” In most data centers today, cooling accounts for greater than 40 percent of electricity usage.

Check out our previous year's TypeRight on e-waste and going green while remaining connected:

From the same MITPress Article:

Under gruelling conditions, miners tirelessly plumb the earth for the rare metals required to make information and communications technology (ICT) devices. Then, in vast factories like Foxconn located in the Global South, where labor can be procured cheaply and legal protections for workers are scant, smartphones are assembled and shipped out to consumers, only to be discarded in a matter of months, to end up in e-waste graveyards like those of Agbogbloshie, Ghana. These metals, many of which are toxic and contain radioactive elements, take millennia to decay. The refuse of the digital is ecologically transformative.

Benjamin Bratton, author of the The Stack: On Software and Sovereignty and The Terraforming, has a different suggestion: In comparison to Instagram's carbon footprint, the environmental impact of planetary-scale computation—including extraction and energy-intensive data centers—is negligible. Human meaning and other cultural activities have a massive environmental imprint. Because human signification leaves the biggest carbon imprint, technology should be utilised to save us from this. The author argues that we should abandon the mistaken belief that defending and creating meaning will protect us against instrumental rationality.

This argument seems like a long way away, but the reality of the impacts are all too proximal.

In Other News

Some updates from the recently concluded democratic exercise:

DEF Updates

At Chanchalguda, Hyderabad, a digital excellence centre by DEF goes beyond CIRCs, and hosts maker spaces, STEM training for girls, and other digital skilling initiatives.

Our digital literacy camps at rajasthan and UP that helps fight disinformation:

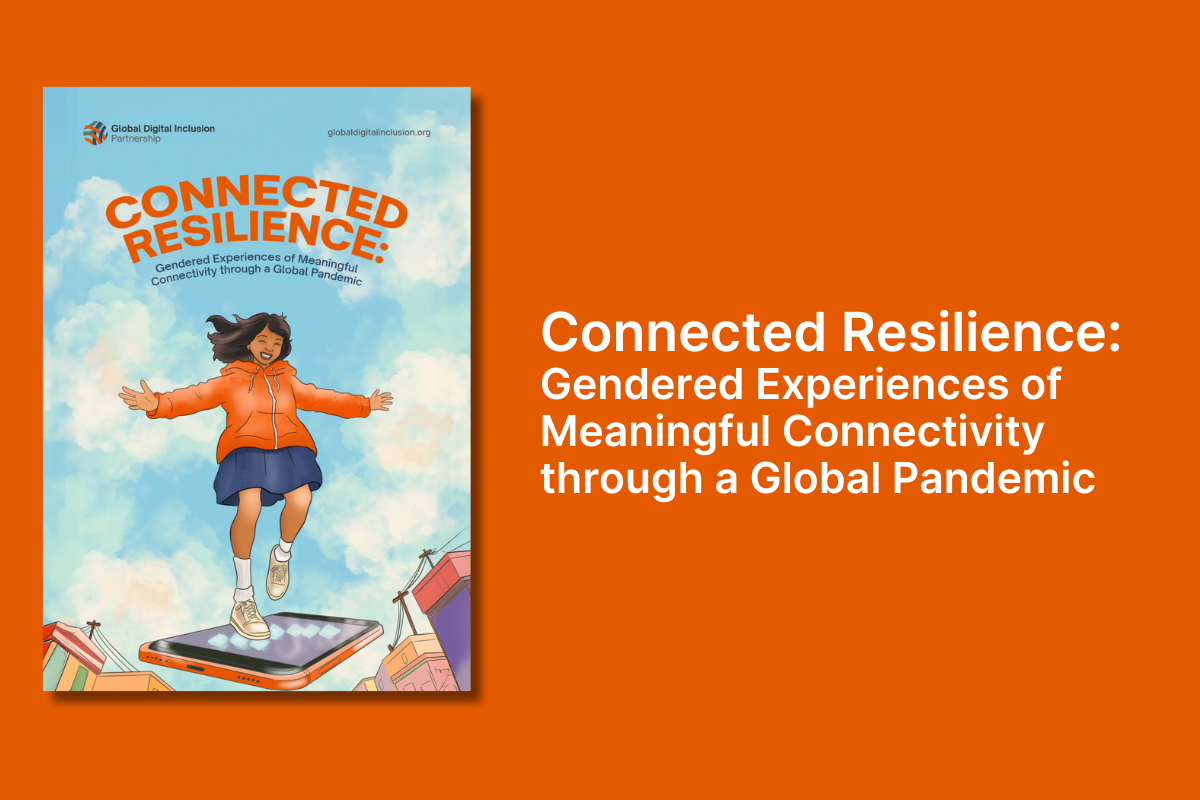

The Global Digital Inclusion Partnership has launched a new digital report - DEF is a partner organisation.

And finally, tune into this podcast:

Until Next time!

.jpg)

might be?](https://sk0.blr1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/sites/1394/posts/714526/dbc8de4c-5c50-411f-aba0-55cfb74a692d.jpeg)

Write a comment ...