The following article and presentation was prepared to share during the panel discussion that was expected to address questions pertaining to the recent increase in interest among international organisations in promoting and protecting freedom of expression, including artistic freedom and protection of artists. It would be interesting to understand if this is linked to a rise in censorship and political oppression, or an increase in the awareness and understanding among these organisations of these challenges, or both. The panel will also explore diverse challenges in this field, as well as opportunities provided by the widespread use of the internet and digital products, and the consequent responses by those targeted by censorship and persecution.

This year, the esteemed Pulitzer Prize for the category of Feature photography was awarded to four Indian photojournalists from the Reuters- Adnan Abidi, Sanna Irshad Mattoo, Amit Dave and the late Danish Siddiqui, “for images of COVID’s toll in India that balanced intimacy and devastation, while offering viewers a heightened sense of place.” The COVID pandemic in India just as much as everywhere else saw an unprecedented rise in fake news and hate-speech targeted at minorities.

Some concerned misinformation around vaccines, or how the virus spread while some were disinformation campaigns targeting muslims after an incident where some devotees had tested positive for the virus, and some were campaigns intended at suppressing the actual scale of impact, toll and fatality the pandemic had during the second wave - and this was what these journalists had brought out.

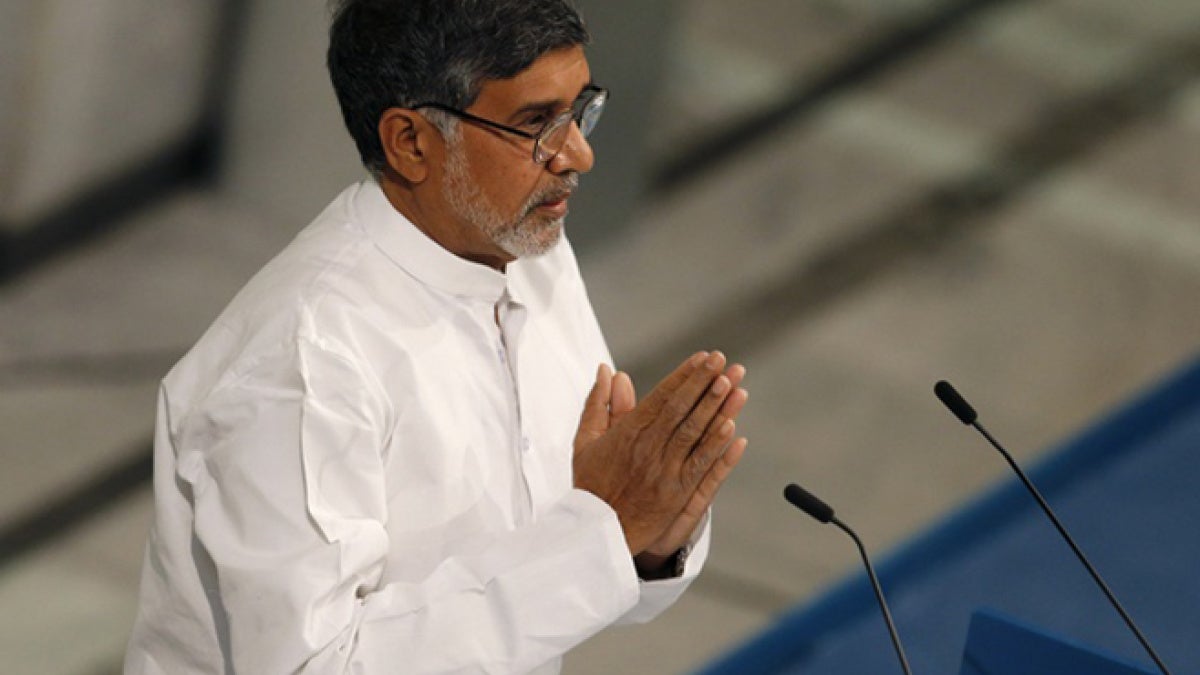

However, just a week before this conference and the award ceremony is being held, one of these journalists, Sanna Irshad Mattoo, from Kashmir, was stopped from travelling to the United States to receive her award.

The past ten years in India has seen a steady increase of assaults on the freedom to express, or express dissent. In fact, it has sharpened for the worse in recent years. For the past government, the newly amended Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), the journalists, cartoonists and other critics arrested under the Section 66A of the Information Technology Act (which was struck down in 2015, however remains to this day in other forms), and impunity given to the armed forces for their extrajudicial killings (and action taken on journalists and activists who exposed this) formed the bulk of these attacks.

2014 saw a far-right nationalist government coming to power and along with it a rise in state targeting free speech as well as mobs doing so with state impunity. As the Human Rights Watch report for that year stated, “In June 2014, an ultranationalist Hindu group organised violent protests in the western city of Pune against a social media post derogatory to some Hindu historical and political figures. Some members of the group, assuming that the anonymous post was the work of Muslims, arbitrarily beat and killed Mohsin Shaikh—who had no links to post—but was easily identified as Muslim because of his prayer cap.”

A trend of continued crackdowns on Facebook and other social media posts, or print magazines that were critical of the establishment could be seen along with several emboldened mobs continuing to threaten publishers and artists- this is something that could be seen today as well. But before we put pinpoint when to place a blame, it's also there that the laws in India were not the best designed for free speech either.

As Penguin publishers said in a press statement in 2014, it was the 'intolerant and rather restrictive laws' that had led them to withdraw a book that caused some controversy with a section of the population (Hindus: An Alternative History, Wendy Doniger). What the publishers were referring to was the First Amendment, which places ‘reasonable restrictions’ to free speech, which was subsequently determined by courts in various instances, thereby setting some precedence to future legal proceedings.

However, fast forward to the lastdecade, and we see how the attacks are one-sided, co-ordinated, and protected with state impunity. Since 2014, four notable murders have been committed in the southern states of Karnataka and Maharashtra: Narendra Dhabolkar, Govind Pansare, MM Kalburgi, and Gauri Lankesh, all suspected killed by one far-right organisation, and murdered for similar motives. Years later, they are still nowhere close to receiving justice, as investigations stall. Following the events, several prominent authors and filmmakers had returned their prestigious awards in protest of the rising intolerance, and the attacks on minorities and free speech.

Since 2017, there has been an increasing use of force in the area of Kashmir, including the detention and jailing of several activists and journalists. Miss Mattoo, who was denied travel, is one of several Kashmiri journalists who had their civil liberties infringed by the army and the government. While some publications like Greater Kashmir or Kashmir Reader now no longer exist following bans and raids, there is a more serious curtail that goes on as the government imposes continuous shutdowns on the region’s internet (and sometimes mobile) connectivity.

This ‘lockdown’ preceded the one that was worldwide since the pandemic, and had the additional component of a communication blackout. Citizens in the valley were restricted using barebones 2G services, even as the pandemic forced people out of normal education modes, and people depended more on online tools for learning, health, information on the pandemic, and more.

While the lockdown was lifted in 2021 February, one and a half years (552 days, to be precise) after it was imposed, internet services still continue to be disrupted in the area citing security reasons, and the people of Kashmir, their livelihoods and their economy continue to suffer. According to the internet freedom watchdog InternetShutdowns.org (a project of the Software Freedom Law Center India), the state alone has witnessed a total of 415 shutdowns of internet services.

Kashmir has it the worst, but it definitely is nowhere easy for the rest of the country either. In a report last year by the media watchdog Reporters Without Borders, India was named one of the five most dangerous countries for journalists, along with Mexico, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Yemen - having witnessed four murders of reporters in just the year of 2021.

In another report by the Committee to protect journalists, seven journalists were named as presently in prison, undertrial under draconian charges: Siddique Kappan, Manan Gulzar Dar, Aasif Sultan, Rajeev Sharma, Tanveer Warsi, and Bhima Koregaon case accused Gautam Navlakha and Anand Teltumbde. Gautam and Anand, arrested in 2020 under a nationwide crackdown on dissenting voices, clubbed as extremist activities, suffer severe health issues in prison with little care from the authorities.

One of their co-prisoners, Father Stan Swamy, had died while in custody, still awaiting trial. Siddique Kappan, who was arrested under allegations of links to an organisation called the Popular Front of India, was on his way to the town of Hathras in Uttar Pradesh, to report on the rape and murder of a young woman belonging to the Dalit community, one of the country’s marginalised social groups.

Rupesh Singh, another journalist from Jharkhand, was also arrested by the central agencies this year on alleged links with the country’s maoist insurgency. The government and their institutions and agencies commonly allege that activists, free-speech advocates, and journalists belong to either ‘urban-naxals’ (having links to the maoist movement), or as being linked to some ‘jihad’, and arrest them under the several draconian laws that puts the onus on the accused to prove their innocence - a process that keeps them in prison for several years. 154 arrests have happened in the past decade, as the Free Speech Collective mentions in their report. Rupesh, along with the undertrial prisoners of the Bhima Koregaon case, were all targeted by the government in surveillance using an Israeli tool known as the Pegasus spyware. When reports of Pegasus broke in a shocking New York Times story, the team also dug up a list of Indians who were targeted, and it is a long list.

In such cases of impunity, where do the people go for redressal? As Fahad Shah, editor of The Kashmirwalla asks in a report by TheNewsMinute, “Journalists have had police raid their homes, smash their cameras and even fire tear-gas shells into their homes … Whom do I complain to?” Bodies such as the National Human Rights Commission or the Press Council or the Press Club take cognisance, but the conclusion is rarely favourable, and increasingly so in recent years. Siddique Kappan remains in jail for two years now, and in cases such as his or Prof. Teltumbde’s, there has been international attention.

As the government puts in new rules, and amendments to old acts - such as the FCRA (Foreign Currency Regulation Act) amendment, the Telecommunications Act amendment, and other key changes to moderate platforms, organisations and non-profits that seek to do work empowering people find it harder than ever to continue. Some of these non-profits also provide grants that keep several independent media platforms running, as well as legal organisations that deal with the barrage of charges stacked upon the activists.

There have been several raids and arrests at the offices of think tanks, research organisations that have been critical of government policies - including Amnesty International India, and Harsh Mander’s organisations including CES.

The lines between ‘Free Speech’ and ‘Hate Speech’ also remain blurred, as the impunity reigns supreme in cases of majoritarian use against other communities. Even as the government places restrictions on several social media content (including many removals), and ban on VPN usage, there have been allegations of other software being employed by the ruling party to manipulate social media, shape narratives and further spread hate, harass people, and polarise communities. This too, happens with impunity.

Rana Ayyub was one such journalist and activist who faced harassment (following her role in criticising the prime minister’s role in the 2002 Gujarat violence against muslims).

In the light of such levels of persecution of activists, somewhat similar to the times of emergency in India in the 70s, the international community is rightly worried about the future of the freedoms of expression and other civil liberties in the country.

As the Freedom of the World report downgrades India’s ranking to only being ‘Partly Free” in 2022, slight improvements in availability and access to digital services and late attempts at bridging the gendered and caste-hit digital divide might seem like not enough to redeem the country’s status.

DEF Updates

First, we would like to inform that the deadlines for applying to several of our ongoing awards have been extended- see these links for more information:

Read this story from SheThePeople on our network engineer Fauziya:

Also, don't forget to join us for the fifth series of Community Networks Exchange 2022, register here:

In other News,

The Wire, a major online news media that has done several strong pieces of journalism, has admitted a flaw in their reporting of several recent stories, allegedly due to a rogue source. While they have apologized, and could be held accountable, the response of immediate raids and seizure of devices on their offices could be seen as a method of threatening any news media that remain critical of the establishment. Here is a statement by DigiPub, a collective of online media outlets on the issue. TypeRight will cover the issue in detail in a following week's chapter.

And finally, we hope all our readers had a prosperous and safe diwali!

Till next chapter next week, Ciao.

might be?](https://sk0.blr1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/sites/1394/posts/714526/dbc8de4c-5c50-411f-aba0-55cfb74a692d.jpeg)

Write a comment ...