This is the second part of the series' Policy - Past & Present: Tracing India’s Development and Justice Debate,' in which we examine the policies on healthcare and education, and assess their inclusivity.

|| PART 2 || Healthcare and Education Policies and Inclusion ||Our post-independence policies on healthcare were mostly fragmented and underfunded, leaving only a few hospitals of excellence in larger cities, while most were pushed to seek care under private hospitals or travel for access. This traces to colonial roots, which established healthcare facilities to either serve the military or the European colonisers, mostly centered in areas where both were larger in number. Perhaps the only other focus would have been epidemic control like TB, Plagues, Cholera, or the likes.

In 1946, the Bhore Committee proposed a universal, free, state-run health service as the cornerstone of India’s welfare state, envisioning comprehensive coverage for all citizens - some of our healthcare policy of (Primary Health Centres) PHCs stem from here, however there has not been as much focus on rural health as the committee had recommended back then. Actual investment in the health sector remains as abysmally low as 1% of the GDP for several decades, with poor services and health infrastructure in most places outside major cities. The services in major cities would also be overburdened because of this lack of distribution.

The private sector has filled in these gaps, slowly commodifying healthcare and making it inaccessible. Programs and initiatives to fight TB, Polio, or Smallpox are some of the largest in the world and remain admirable victories despite the lack of funding. The reasons generally cited for the poor infrastructure are resource constraints, which brings the question of what spending and welfare policies have focused on. Kerala and Tamil Nadu might offer contrary examples to this trend, with state funding consistently prioritising primary healthcare facilities and effectively achieving lower infant mortality rates and higher life expectancies. Post-liberalisation there was an even lower public spending at the national level, with active encouragement of private hospitals which had proliferated around the time. The more recent policies like Ayushman Bharat that aim at universal coverage rely heavily on the private sector for delivery.

Even as incomes saw a fairly stable improvement in the recent statistics, the metrics of the (Human Development Index) HDI show deficits in health and education. Even within this, as health saw a marginal increase, education further declined. This probably has to do with the shifts in priorities during the COVID-19 pandemic. We have been able to address access to basic health facilities, at least broadly. However, the pandemic also showed us the reality of how ready our health infrastructure is to address health emergencies. Without financing this, we cannot achieve the readiness we require to be a robust collaborator in international health endeavours. The specific significance of this issue in public health lies at the intersection with the global climate crisis, where climate change brings forth conditions where certain disease vectors survive, exacerbated by lack of access to clean water, heat waves, and pollution. All of these require us to move beyond primary healthcare as the sole agenda of health, and these are policy gaps in addressing a large potential public health crisis at the intersection of climate change and planning.

Inclusion and Divides in Education- Digital and Social

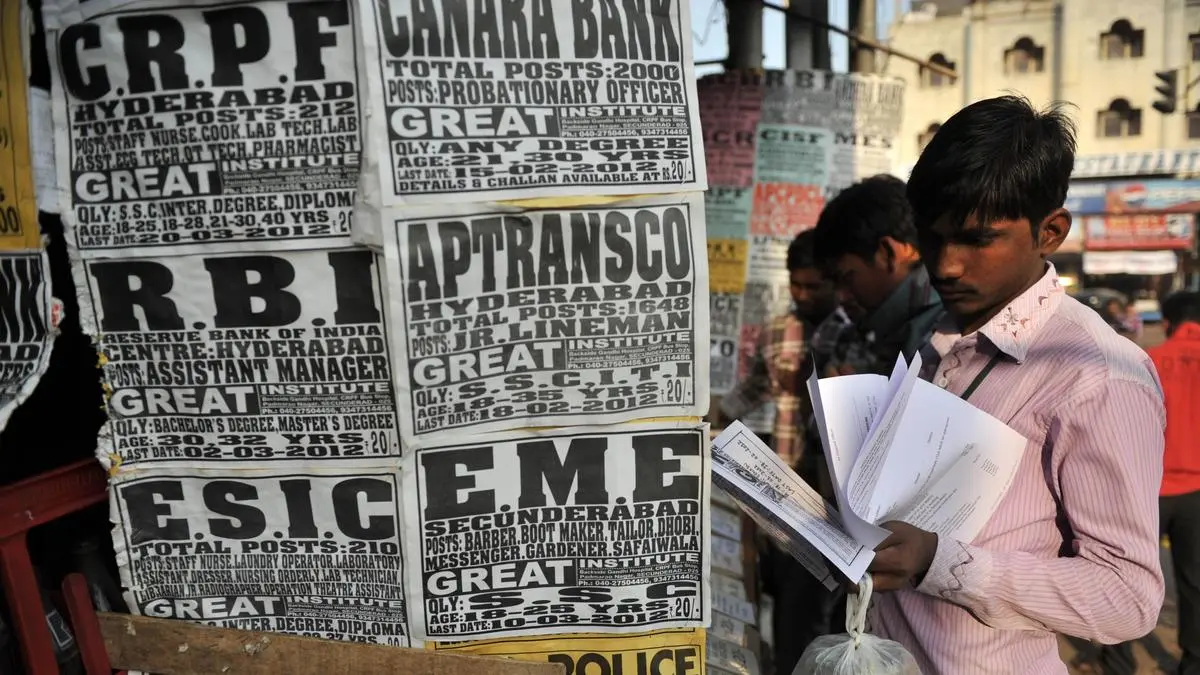

Statistically, 1.1 billion people are connected to the internet in the country, numbers that have leaped in the past few years since the pandemic. These numbers are definitely good, and are a result of favourable policy in the past decade - including Bharat Fiber, PMWani, but also, a compelling digitisation push that has often left several people in the dark. For a lot of people of this 1.1B statistic, real, meaningful connectivity is hard to come by. The forced part of this push is that increasingly services that are basic like food, payment, banking and even employment money has become available only to those with access to both formal banking as well as the digital know-how. As a result, it is essential to have policies that help people access the internet, learn how to use it effectively, and avoid online scams.

It has only been around 30 years since the internet reached India, and due to the costs of access and other infrastructural issues, adoption remained slow. The National Optical Fibre Network initiative, planned in 2011 (and since then renamed BharatNet) is one such Special Purpose Vehicle that intended to connect all 1.15 lakh Gram panchayats in ten years’ time, allowing the panchayats to enable telemedicine and e-governance. Only 194,000 of 640,000 villages connected by 2023, missing deadlines due to logistical hurdles and poor planning, and due to faulty hardware and maintenance issues. The PM-WANI (Wi-Fi Access Network Interface) is a better-utilised scheme for last-mile connectivity, set up in an entrepreneurship-focused model, requiring less infrastructure than the standard fibre networks. Financial reforms (e.g., rationalized spectrum fees, easier Right of Way approvals) have enabled rapid deployment of 4G and 5G networks. PM-WANI’s strongest opposition were telecom companies, who have contributed to the adoption leap with dropping data costs in the past decade. While there was initially a strong competition in the telecom market, recently they have collapsed into a sort of duopoly.

This digital boost has had its impact in education, especially since and during the pandemic. The statistics of increased access to smartphones and the internet in rural India is to be acknowledged, however, this access alone can not guarantee effective education. Similarly, an increase in aggregate enrollment, despite the pandemic, does not necessarily entail attendance in classes.

There have been proposals to revamp the current education model to include more career-focused exit options because of the uncertainty AI will bring to the job market in the near future - because already some statistics show that half of the indian youth are unemployable. Specifically targeted digital literacy programs that focus on employability and developing basic capabilities must be coupled with the access and inclusion policies. Remedial classes that focus on fundamental skills and not the NCERT standardised curriculum should be explored in this light.

All of these policies brought together with the development of digital infrastructure might help counter what Sen feared as missing the development window with out population peak. There is a general agreement that the country should have been poised to reap our demographic dividend. However, our economy is growing without absorbing the labour from agriculture to industry as with other industrialised nations. Policy and research must look into how we can work on the demographic dividend. To see why India probably will not see the same leap as the rest of Asia, has to do with our policy in education over time. While earlier commissions that built into the first few five-year-plans like the University Education Commission (1948) and the Kothari Commission in the 60s advocated for universal education and three-tiered structure, it would not be until the 2000s that the Right to Education would be formalised and mandated. Some southern states, as with health, performed better both due to focus on investing in public education post-independence as well as other infrastructure that existed prior to 1947.

The shift away from government spending in education since the nineties is apparently modelled off developed nations like Britain and the US.However, since the 1960s, government spending on education in the United States has exceeded 5% of GDP; higher education spending has never been less than 1% of GDP and has occasionally reached 2%. Without this spending, they might not have reached the status of education they now have. Also interestingly, the present student debt in the US, since they have made this move into even stronger privatisation, runs into a couple trillion dollars, close to half of India’s entire GDP. The policy question to ask is whether this debt is something we would prefer to chose over government spending, given the scale of investment in education in the country. How can policy look into this slow transition into life support for most public universities while meaningfully answering questions of access and exclusion? Can we really monetise the benefits like social mobility for marginalised populations and a reduced inequality?

India’s inadequate investment in health, education, and social services severely undermines its ability to benefit from the demographic window, which can only be realized if the workforce is healthy, educated, and skilled.

But as noted above, welfare policies go hand-in-hand with a just tax system. When the larger masses are subsidising the losses of the wealthier class through indirect taxation, whose welfare do these policies seek to ensure? And when welfare schemes are envisioned, how do the most deserving get them? The next part of this series will look at a history of policies in the justice system.

REFERENCES

CDPP Conference Report, 2025

Duggal, R, 2001. EVOLUTION OF HEALTH POLICY IN INDIA. CEHAT

Hooda, S. HEALTH SYSTEM IN TRANSITION IN INDIA Journey from State Provisioning to Privatization. Pluto Journals

Sen & Dreze, 2013. An Uncertain Glory: India and its Contradictions. Princeton University Press

DEF Updates

At WSIS+20, Dr. Arpita Kanjilal and Abner Manzar from the Digital Empowerment Foundation joined global leaders in a Partner2Connect (P2C) interactive workshop focused on bridging the digital divide and building an inclusive AI ecosystem.

DEF is anchoring a collective, transregional civil society campaign on platform accountability, supported by the ARISE (Accountability and Responsibility in South’s Ecosystems) Community.

We’re joining hands with Point of View, Mumbai and 212+ organisations across the Global South to demand accountability from Meta (Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp) for enabling hate, online violence, caste based abuse, erasing LGBTQ+ and disabled voices, and platform bias.

The 7th DigitalCitizenSummit (DCS) 2025, in collaboration with Centre for Development Policy and Practice, invites students, researchers, and practitioners to present papers on the theme: 𝑷𝒆𝒐𝒑𝒍𝒆 & 𝑷𝒍𝒂𝒕𝒇𝒐𝒓𝒎𝒔: 𝑳𝒆𝒕’𝒔 𝑻𝒂𝒍𝒌 𝑨𝒄𝒄𝒐𝒖𝒏𝒕𝒂𝒃𝒊𝒍𝒊𝒕𝒚

📍 T-Hub, Hyderabad

📅 14–15 November 2025

See you next week!

might be?](https://sk0.blr1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/sites/1394/posts/714526/dbc8de4c-5c50-411f-aba0-55cfb74a692d.jpeg)

Write a comment ...