Dr Dhiraj Singha, a researcher at the Digital Empowerment Foundation looks at a three-year research on the SoochnaPrepreneur model, which shows how enlisting rural women as SoochnaPreneurs increases the value of services, broadens their reach to consumers, and stimulates local economies.

This review explores a transformative model of grassroots entrepreneurship in rural India that combines digital inclusion with social empowerment. It draws upon a detailed empirical study and the pioneering efforts of the Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF). The review highlights how rural women, when empowered as SoochnaPreneurs, can bridge last-mile gaps in access to information, government services, and digital resources. It also briefly describes the impact of integrating women into community-driven service delivery models. Beyond improving consumer acquisition and value delivery, the review reveals how women microentrepreneurs foster gender inclusion, influence social dynamics, and catalyze wider community benefits, even boosting the performance of their male counterparts. For development practitioners and researchers seeking scalable models sensitive to local realities, the SoochnaPrepreneur experience provides valuable lessons. This report aims to contribute to ongoing dialogues around inclusive digital ecosystems, equitable entrepreneurship, and sustainable rural development.

The Soochnapreneur model has emerged as a compelling approach for digital inclusion, not only by bridging the digital divide but also by developing a locally rooted ecosystem of entrepreneurship, accessible public services, sustainability, and strengthened physical infrastructure. When digital capacity is placed in the hands of a woman, particularly one with the motivation and entrepreneurial drive to assert her identity, it catalyzes a ripple effect of empowerment. The Soochnapreneur becomes a critical node of connectivity in her village or panchayat, enabling marginalized communities to access information, government entitlements, financial services, and digital literacy. The effectiveness of this model as a scalable approach to digital inclusion and grassroots empowerment has been rigorously documented through a three-year empirical study.

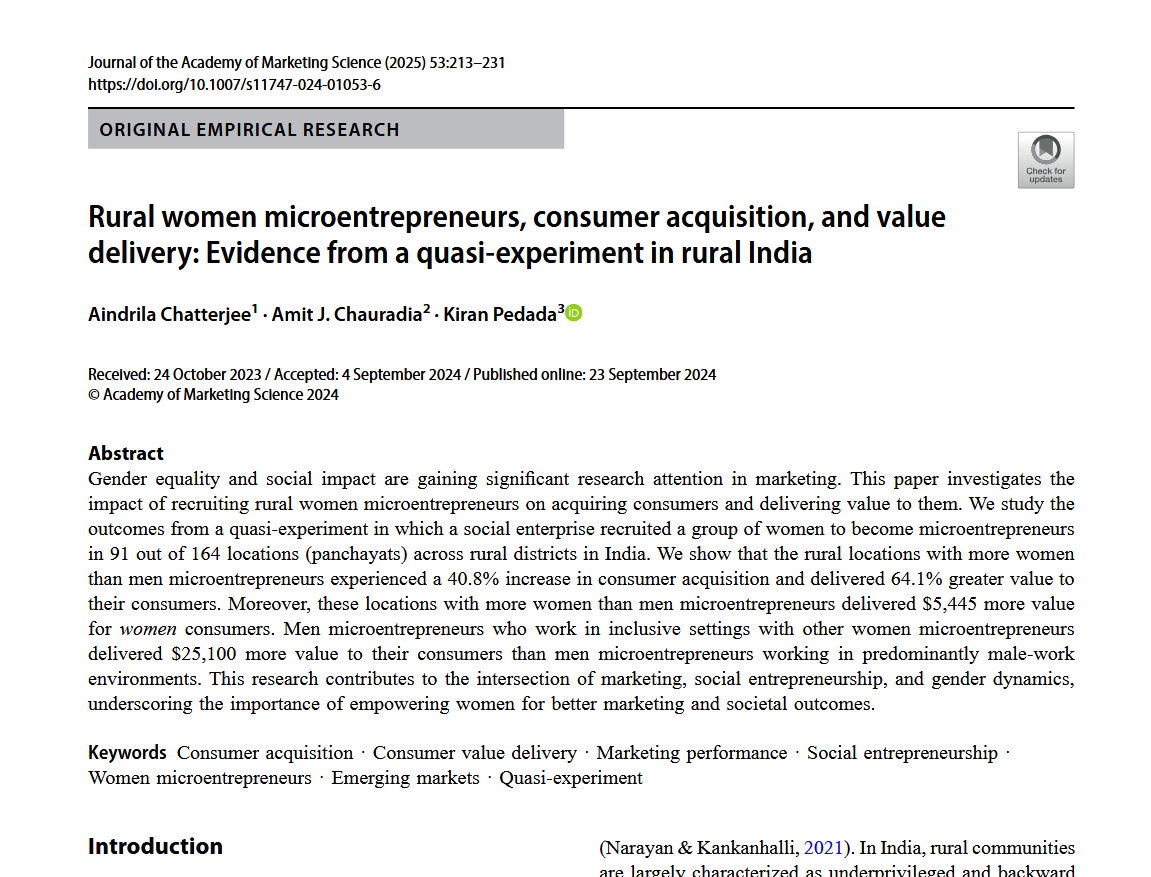

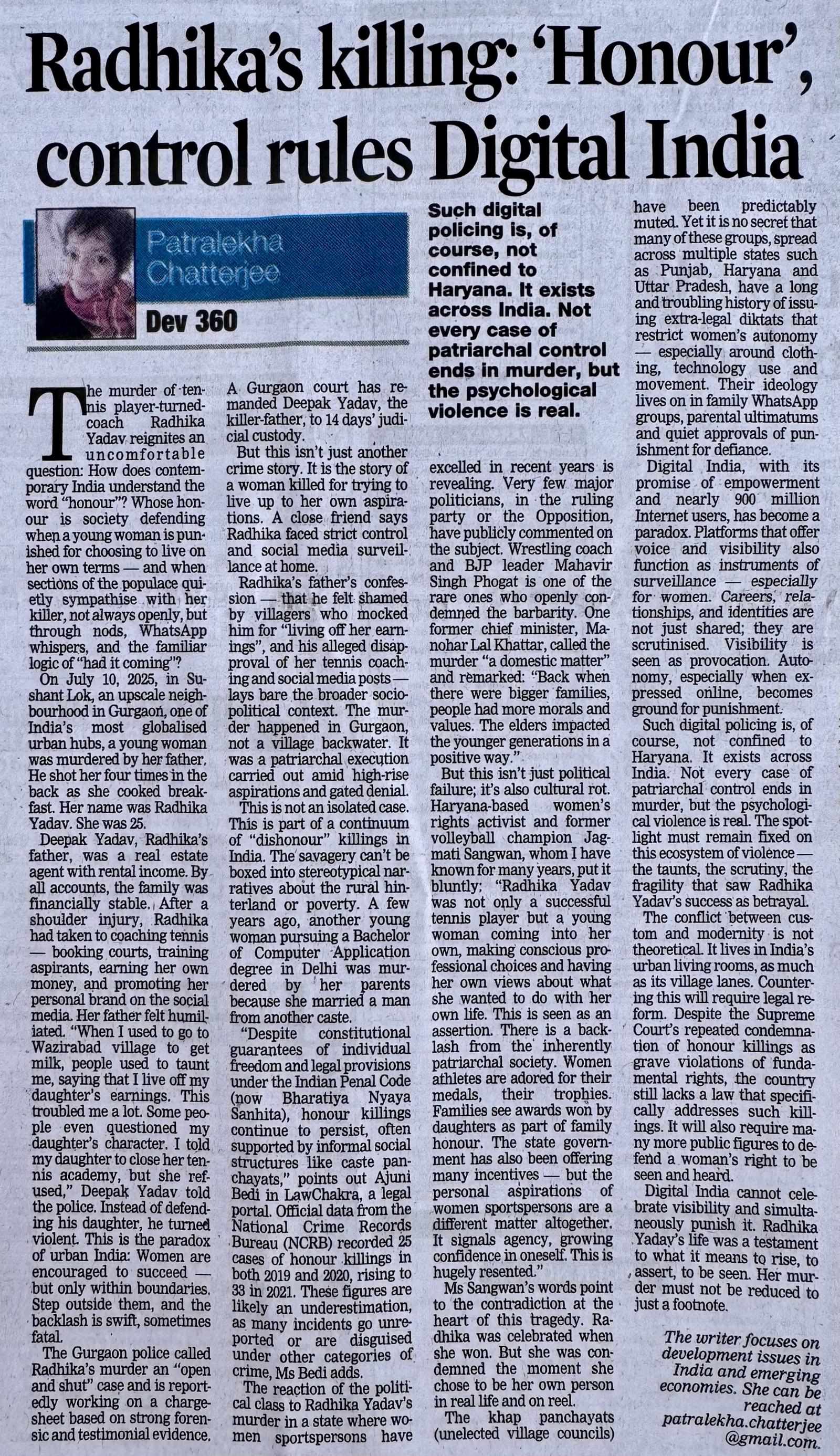

The article "Rural Women Microentrepreneurs, Consumer Acquisition, and Value Delivery: Evidence from a Quasi-Experiment in Rural India," published by the Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science on September 23, 2024, was authored by Aindrila Chatterjee, Amit J. Chauradia, and Kiran Pedada. They argue that recruiting rural women microentrepreneurs (RWM) not only improves consumer acquisition and value delivery in emerging markets but also motivates male peers to perform well, which further contributes to larger Sustainable Development Goals like gender equality and reduced inequalities. The study is situated within a digital inclusion initiative of the Digital Empowerment Foundation (DEF), a social enterprise known for leveraging digital technology to empower marginalized communities. Specifically, the authors evaluate DEF's SoochnaPreneur (SP) program as a real-world context for their quasi-experiment. This program deploys locally identified, highly driven, and socially conscious individuals as social entrepreneurs (SPs) in villages or Panchayats to bridge last-mile gaps in welfare services and trusted information access through digital connectivity and infrastructure. The findings of the empirical study contribute meaningfully to the literature surrounding marketing, gender dynamics, and social entrepreneurship. This essay reviews the study's core arguments and theoretical underpinnings, and highlights areas requiring further inquiry. Concurrently, it expands the context to consider how initiatives like SPs operate at scale and how the results inform ongoing efforts to close India's gender digital divide.

The authors employed a quasi-experimental design using a difference-in-differences (DID) approach to compare outcomes between intervention (treatment) areas and control areas. The intervention areas experienced a policy shift in 2018 that increased the recruitment of women microentrepreneurs, while control areas maintained a traditional male-dominated recruitment strategy. This design, supplemented by qualitative interviews, allowed them to investigate three questions: (1) How does a greater presence of RWMs affect consumer acquisition and overall value delivered by the social enterprise? (2) What is the impact on the value delivered specifically to women consumers when RWMs are involved? (3) How does the presence of RWMs influence the performance of male microentrepreneurs in the same network? Drawing on data from DEF's interventions, the study tracked 285 unique microentrepreneurs (SPs) across 164 panchayats in six districts over a 36-month period (January 2017 to December 2019). In total, 91 panchayats served as intervention areas (with more women recruited post-2018), and 73 served as control areas (continuing with mostly men). Intervention districts included places like Alwar, Guna, and Ranchi, where DEF's policy change in early 2018 significantly increased the intake of women entrepreneurs.

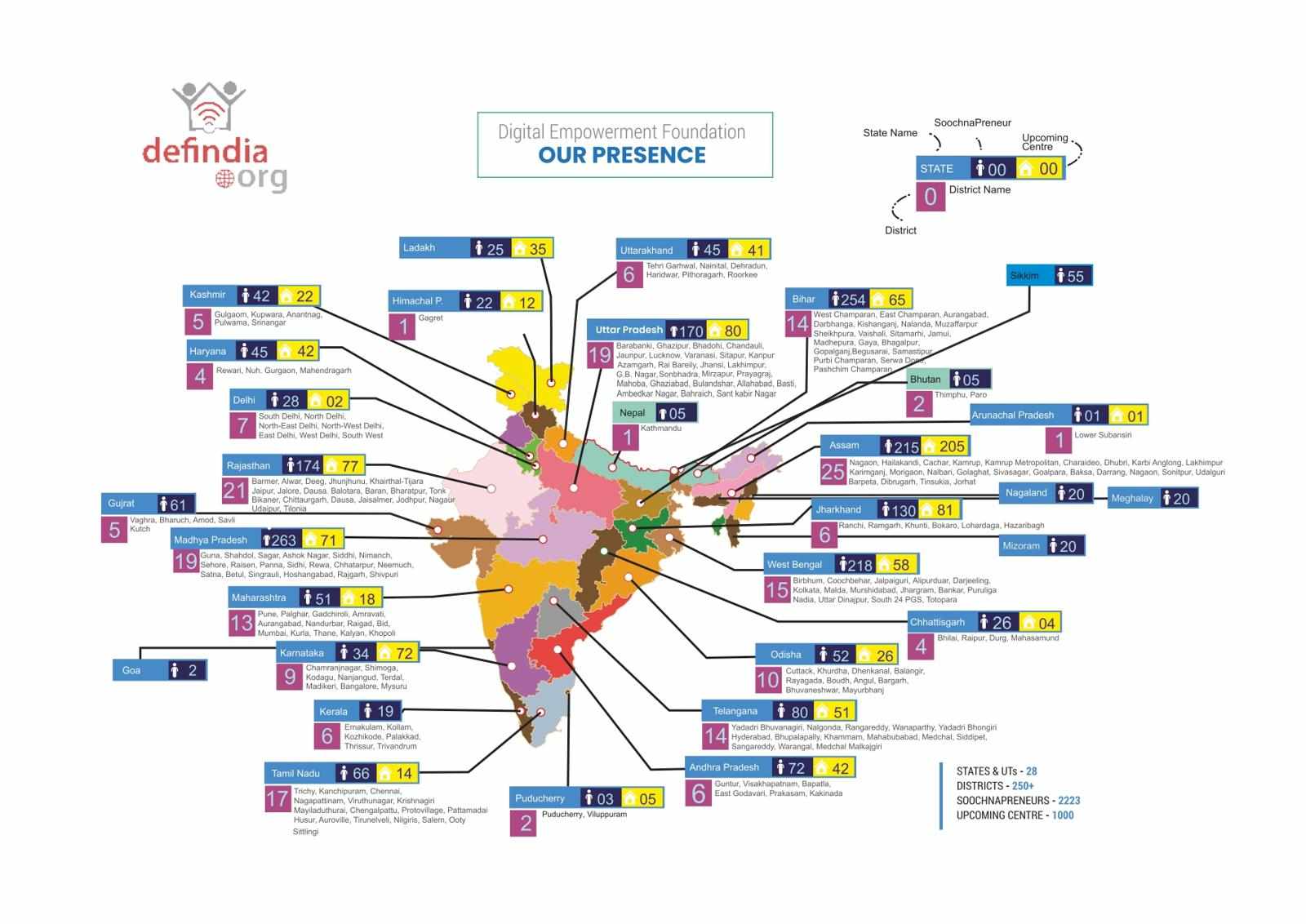

SPs are a part of DEF's flagship program, which aims to provide last-mile access to critical information and services in rural India. DEF equips these village-level microentrepreneurs with internet-enabled digital devices, a multilingual mobile app, and training on assisting citizens in availing various government welfare schemes and digital services. A SoochnaPreneur helps identify eligible families for welfare schemes, raises awareness about entitlements (such as health insurance, scholarships, rations, and pensions), and assists with the paperwork and online form submissions required for enrollment. For each successful enrollment, the SP charges a nominal fee of about ₹200 (approximately $2.40 USD), a sum kept affordable by DEF's guidelines as compensation for time and service. This micro-franchise model allows entrepreneurs to earn a livelihood while delivering value in two ways: directly connecting villagers to financial benefits (cash transfers, subsidies, insurance payouts) and providing convenience by saving them travel and bureaucracy (preventing lost wages from manual trips to distant government offices). By 2019, hundreds of SPs were operating in many states, including Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Bihar, and Odisha, demonstrating the initiative's scale and its contribution to both digital and financial inclusion. This background sets the stage for the study to examine how the inclusion of women in this model impacts the results.

The findings indicate that treated locations where women were brought into the entrepreneur workforce significantly outperformed control areas in terms of consumer reach and service delivery. Specifically, the intervention villages experienced a 40.8% increase in consumer acquisition and delivered 64.1% greater value to consumers compared to villages with only male entrepreneurs. Furthermore, women consumers in these gender-inclusive areas received an additional $5,445 worth of value (over the study period) when served by women microentrepreneurs, as opposed to being served by men. Interestingly, the presence of female entrepreneurs had a spillover effect on their male counterparts, with men in mixed-gender teams delivering approximately $25,100 more value to consumers than men operating in all-male environments. All three findings were statistically significant and substantively meaningful. In essence, bringing women into the fold not only directly improved outreach to consumers (especially female consumers) but also indirectly boosted the productivity of men in the network.

The authors attribute these impressive outcomes to women's "communal traits" such as empathy, patience, and care, and the shared identity women entrepreneurs have with women consumers, invoking social role theory to explain the higher trust and rapport in those interactions. Qualitative interviews with 14 RWMs (the women Soochnapreneurs) reinforce this, as women spoke of how their active engagement earned social recognition and began to chip away at patriarchal norms in their communities, becoming known as entrepreneurs in their own right, rather than just someone's wife or daughter-in-law. By contrasting rural India, home to over 800 million people, with more developed urban markets, the article fills an important gap in marketing literature. It highlights the role of rural gender norms (e.g., women's traditional roles as caregivers) in explaining why women's economic engagement can generate disproportionate social impact. In line with social role theory, culturally prescribed gender roles mean that women entrepreneurs often approach consumers with a community-centric mindset rather than a purely transactional one. Their "communal nature," as the study calls it, helps build trust and rapport, especially with women customers who may be dealing with sensitive issues like menstrual hygiene or who have been historically excluded from formal financial systems. The SPs' ability to bridge information gaps for such marginalized groups is a key mechanism behind the quantitative metrics.

Equally interesting is the ripple effect observed on men. Male microentrepreneurs, when working alongside women, either stepped up their performance due to healthy competition or perhaps learned new customer engagement approaches by observing their female peers. This dynamic demonstrates how gender affects group entrepreneurship and suggests that teams including people of all genders can create a virtuous loop of peer motivation and a wider client base, which benefits the business as a whole. These results are encouraging because they demonstrate a pathway to closing the gender digital divide in India. Rural women in India have historically been excluded from the digital revolution; as of 2019-21, only one in three women in the country had ever used the internet, and in rural areas, men are twice as likely as women to be online (49% of men vs. just 25% of women). This gap is due to various reasons, including social norms that limit women's mobile phone usage, lower literacy rates, and limited access to ICT infrastructure. The SP model directly addresses some of these problems by making women digital change agents in their villages. When a local woman becomes the go-to person for accessing e-governance services, it not only empowers her but also makes other women in the community more comfortable engaging with technology and public services. Many female consumers who might hesitate to approach a male agent or travel to town for a government office are now served at their doorstep by a woman they trust. This "women-helping-women" dynamic is particularly helpful in situations where purdah (gender seclusion) or safety concerns make it difficult for women to move around. The initiative leverages women's social networks to provide female beneficiaries with digital benefits, including the ability to fill out forms online, make digital payments, and get information through mobile apps, which they otherwise might not access. In terms of digital and financial inclusion, this creates a positive feedback loop: as more women agents come online and gain digital skills, they bring more women customers online (at least indirectly, to obtain services), which gradually normalizes technology use among rural women. The study's outcomes thus serve as encouraging evidence that closing the gender gap among service providers can help close the gap among end-users. In a country that accounts for half of the world's gendered digital divide, such evidence-based guidelines are extremely valuable. They suggest that policymakers and development organizations should invest in programs that train and support women to be last-mile digital service providers—a strategy that can make Digital India more inclusive by design.

This approach and its findings strongly resonate with India's broader Self-Help Group (SHG) movement for women's empowerment. For decades, SHGs—grassroots collectives of 10-20 women engaged in savings, credit, and microenterprise—have been a cornerstone of rural development, successfully aiding the financial inclusion of women through programs like the SHG-Bank Linkage scheme. For example, the government's National Rural Livelihoods Mission (NRLM) builds on SHGs to train "Bank Sakhis" (female community bankers) who act as banking correspondents in villages. These women, much like SPs, use digital tools (handheld devices, tablets) to offer services such as depositing money, withdrawing cash, transferring funds, and even enabling e-commerce and online education in remote areas. The SHG model has already demonstrated the power of collective female entrepreneurship; it is arguably the largest women's empowerment project in the country, growing steadily at about 10% annually and reaching millions of women. The SPs initiative adds an explicit digital and information-services layer on top of this model. It transforms individual women (or groups of women) into infomediaries—individuals who not only manage finances but also connect the community with knowledge and entitlements. The study under review aligns with and reinforces this trajectory. Its evidence that women entrepreneurs can drive superior outcomes provides empirical support to expand such integrations of SHGs with digital technology. One can imagine synergistic policies where SHG members are trained to also become SPs or Bank Sakhis, thereby combining the social capital of SHGs with the tech-driven approach of DEF. Such a convergence could dramatically enhance both economic and social empowerment outcomes, with women gaining income and status as entrepreneurs, households gaining easier access to welfare schemes, and communities witnessing normative change as women take on public-facing leadership roles.

Despite its valuable contributions, the article has limitations, leaving room for further inquiry. Methodologically, beyond the technical design, the ethical framework of the study appears underdeveloped. The absence of reflexivity raises concerns about possible neo-colonial dynamics, wherein foreign-funded actors "experiment" on rural women under the banner of rescuing them. This is a wider pattern in positivist development research, where the drive to produce generalizable policy insights can overshadow the need for community agency and ethical stringency.

Theoretically, the article heavily relies on social role theory, positing that women's communal attributes (nurturance, empathy, altruism) explain their superior performance in delivering value to consumers. While this interpretation is consistent with existing gender-and-entrepreneurship research and resonates with narratives from the field, it also walks a fine line. Emphasizing women's innate caring qualities can slide into essentialism, reinforcing the trope that women are "natural caregivers" whose entrepreneurship is an extension of their social roles. The focus on shared identity (women serving women) adds nuance by highlighting how representation matters—rural women consumers feel more comfortable and trusting with someone who understands their context. Yet, even this risks a deficit narrative if not handled carefully, implying that the primary reason marginalized women lack services is the absence of female providers, sidestepping the broader institutional failures that necessitate a special program in the first place.

The positive spillover effects observed among male entrepreneurs also merit deeper theorization. The authors speculate these effects might arise from competition (men feeling challenged to keep up) or social learning (men emulating the successful practices of their female colleagues). Both explanations are plausible and align with broader theories of behavior change. Future studies should also inquire about how this learning or competition manifests. Do men adopt a more community-engaging style after observing women, or do they simply work harder once women break the ice in conservative villages? How do men acknowledge learning from their female peers?

The study's operationalization of "value" delivered is innovative in that it quantifies welfare access (monetary benefits disbursed, time saved for consumers) using data tracked via a mobile app. However, such conclusions also need to discuss the risk that this quantification can slip into the neoliberal logic that dominates much development discourse. By translating empowerment into rupees saved or minutes freed, the analysis may inadvertently validate the idea that improvements are most legible when expressed in market-centric metrics. With such theoretical underpinnings, it is also important to ask a few follow-up questions: Did these women, after three years, gain greater say in household decisions? Did their new roles reduce social stigma or shift patriarchal attitudes among their family members? Or, conversely, did taking on this additional "job" merely add to their burdens (the notorious double burden of work and domestic duties) without relieving them of any traditional responsibilities at home? The value delivered to consumers is evident, but what is the value retained by the women beyond modest income and self-reported esteem? If an empowerment intervention does not tackle issues like land rights, legal awareness, or redistribution of care work, can it truly be transformative, or is it destined to remain a piecemeal fix?

The findings also underscore the need for emancipatory frameworks like intersectionality in future research. These should explicitly account for how caste, religion, and class intersect with gender to shape women's experiences. Rather than treating these as control variables to neutralize, future research should center them as core factors that co-constitute agency. For example, a follow-up study could examine which women were more likely to thrive as SPs and why—perhaps Dalit women faced different hurdles or Muslim women needed different support—thereby tailoring interventions more finely. In short, there is room to bridge the gap between econometric rigor and the "messier" work of social change. The study is compelling and serves as a practical guidepost, demonstrating that empowering rural women as entrepreneurs and information leaders is not just about checking a diversity box—it actively reshapes communities and markets for the better.

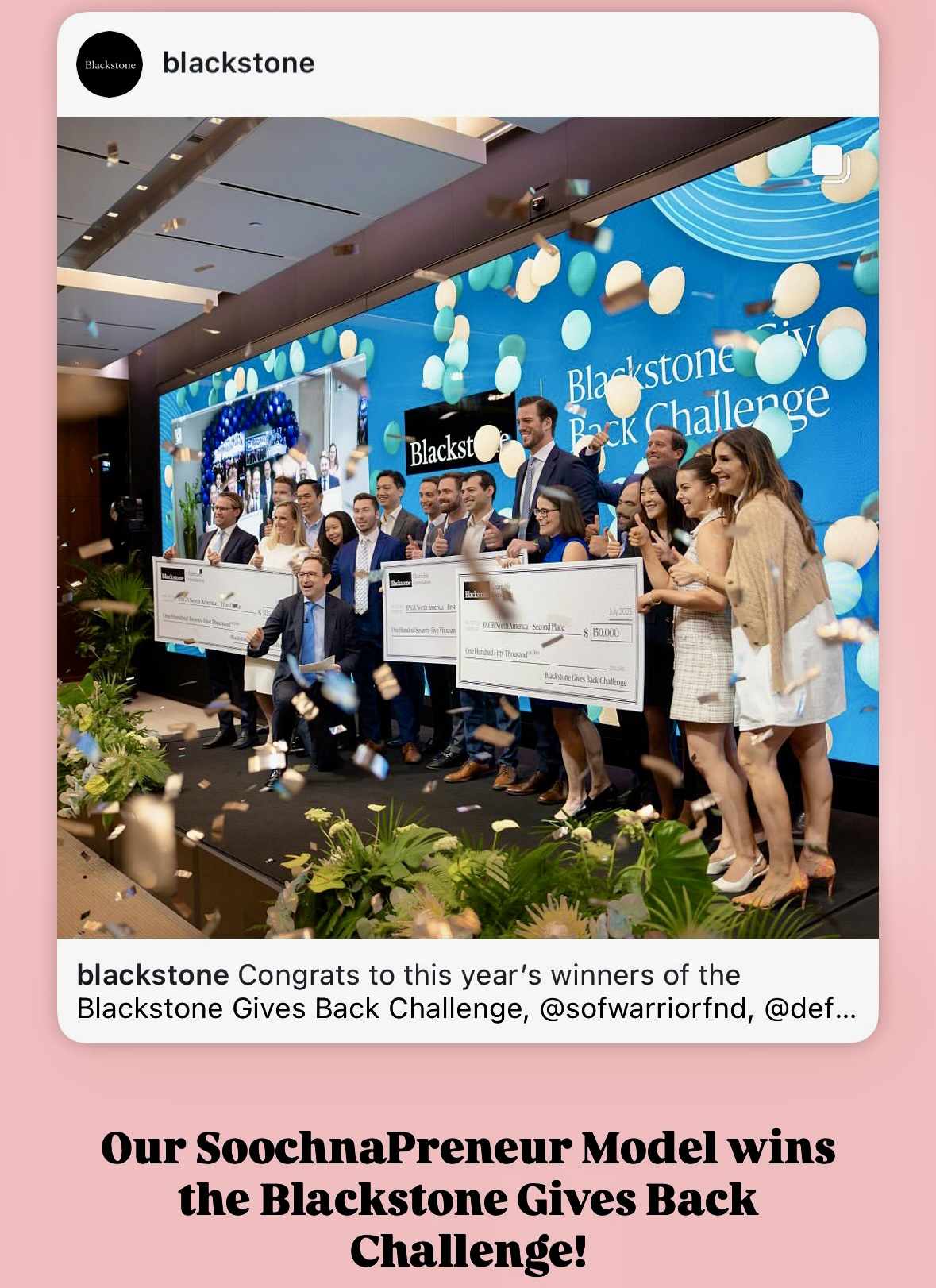

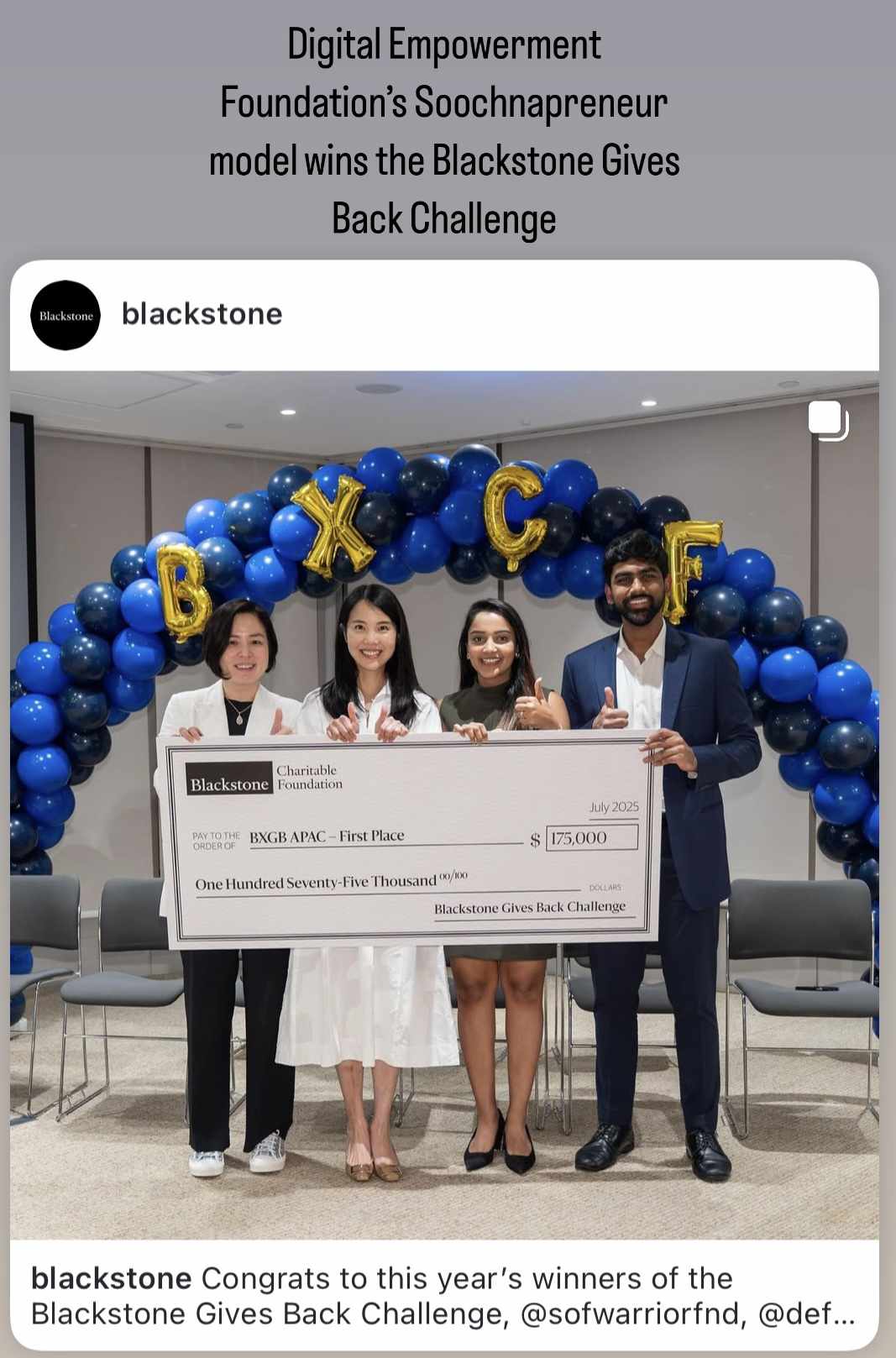

As a matter of record: SoochnaPreneur model and program is endorsed by following:

- World Bank, who conferred an award to SoochnaPreneur

- United Nation’s WSIS has conferred award to SoochnaPreneur

- Qualcomm has funded and endorsed Soochnapreneur model

- EquallyAble has been funding Soochnapreneur

- USAID, USIPI, Blackstone, Telangana Government, Ministry of Communication & IT, Internet Society Foundation, European Union, Nokia, Accenture, Zoom, Standard Chartered

DEF Updates

Presented by MXR.world (‘mixers across the world’), this engaging session during the Hyderabad BizLitFest will feature startups and storytelling! There will be pitches by 5 AI startups, inputs from investors and domain experts, and roadmaps for scale. A week before the session, a masterclass on storytelling for founders based on The Changemaker Story Canvas will be conducted.

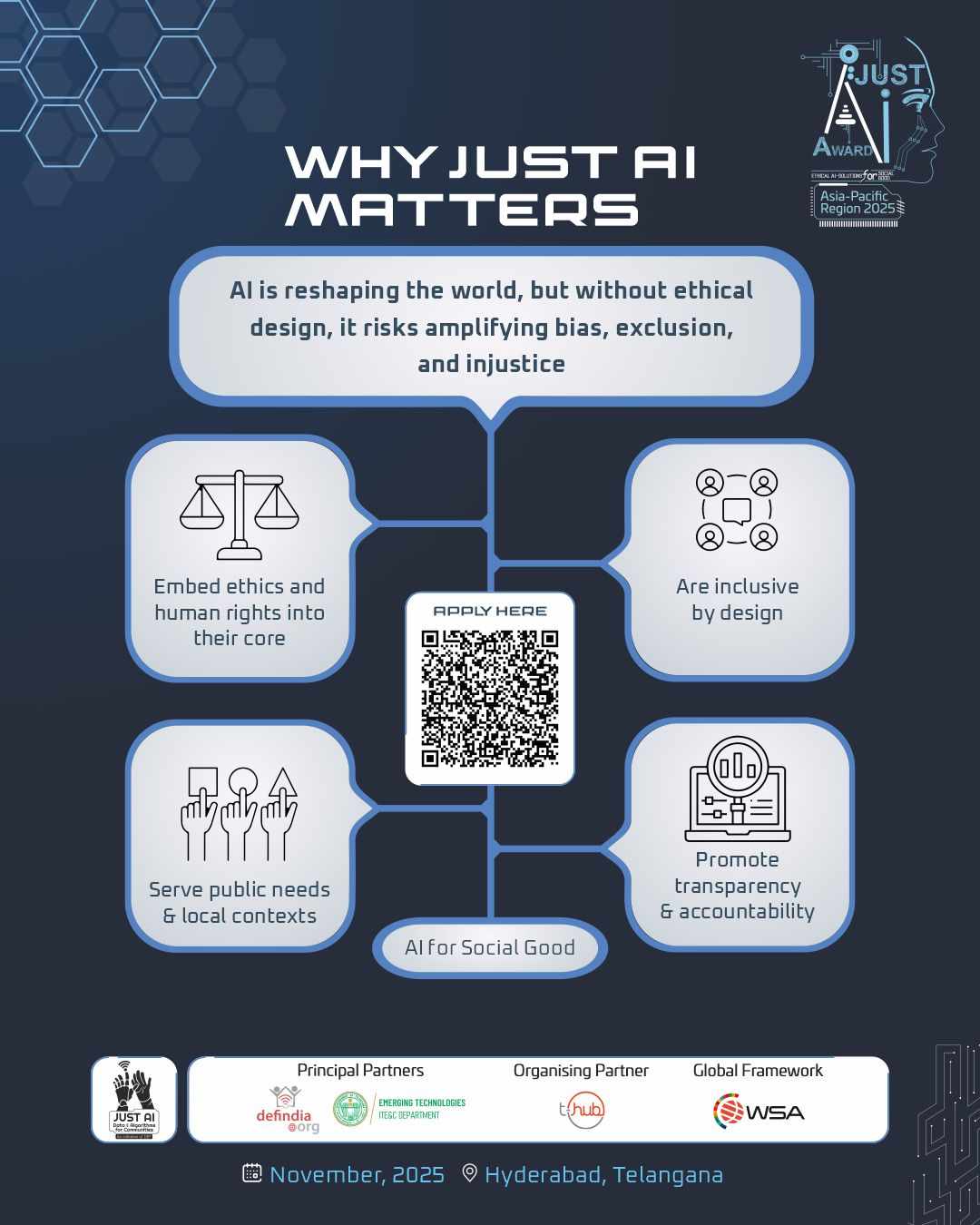

In partnership with the Digital Empowerment Foundation, the session will also focus on key issues of digital inclusion in the Age of the Algorithm where ethics, responsibility, transparency, and accountability need to more adequately addressed. Updates from their Just AI Initiative will be presented, along with a call to action to factor in environmental and social consequences of AI.

DEF featured in Marathi News:

Apply now for the Just AI awards hosted by DEF and the Telangana Govt:CN

CNX 2025 is calling for ‘Call for Sessions’ from across Asia-Pacific countries

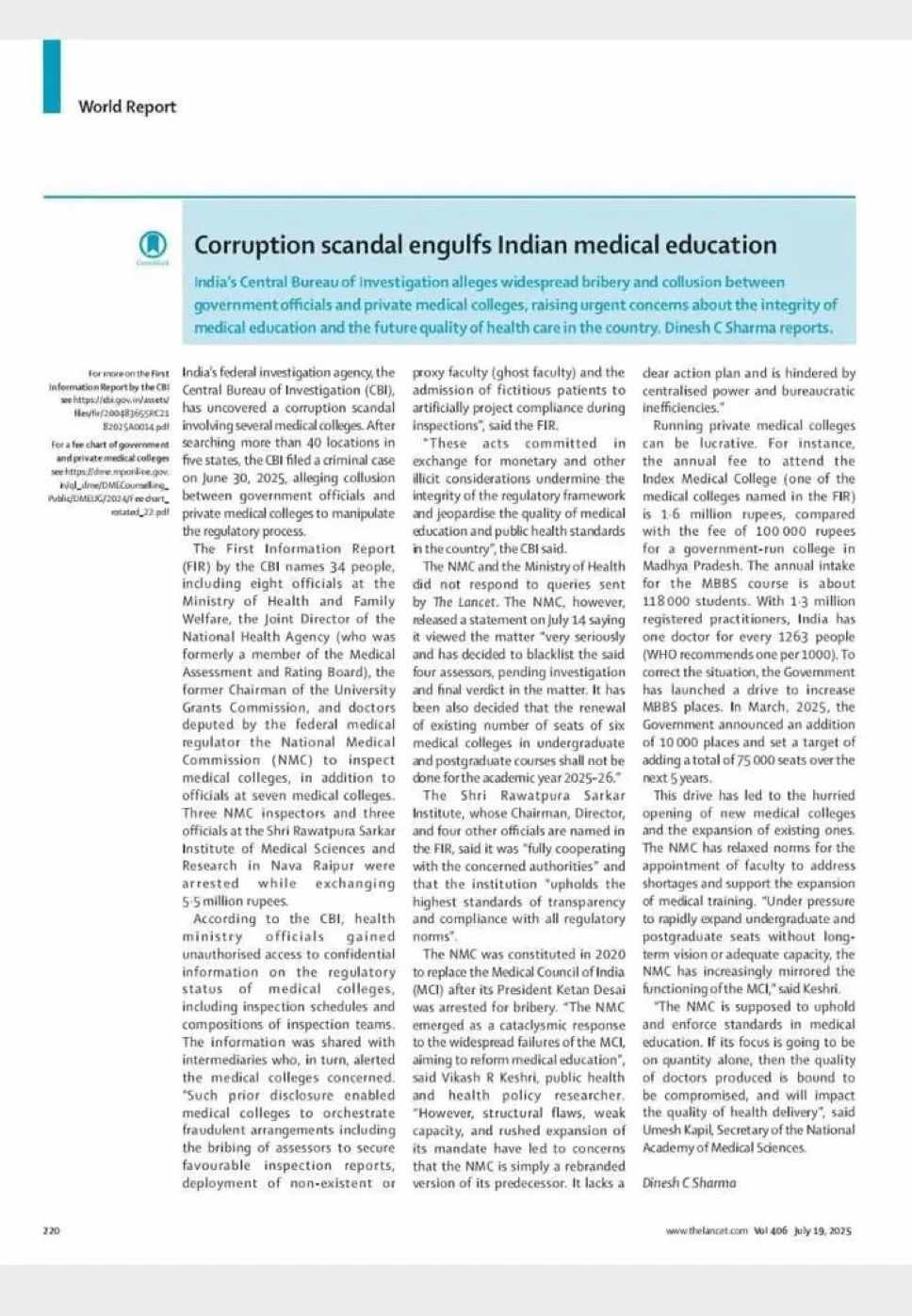

What are we reading

More next week…

might be?](https://sk0.blr1.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/sites/1394/posts/714526/dbc8de4c-5c50-411f-aba0-55cfb74a692d.jpeg)

Write a comment ...